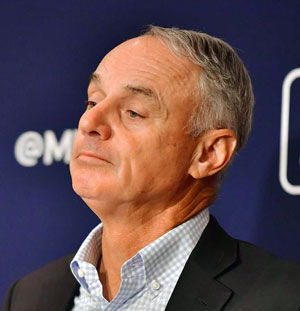

Tag: Rob Manfred

Baseball notes

Prior to last year, when I chose to abandon it mid-season, I was running a website all about Your Seattle Mariners baseball club. If it was still up and running, this would have been a full couple of weeks of posting there thanks to the annual Major League Baseball trade "season" that came to a close on August 1st. A lot of movement there to cover.

For better or worse—mostly better, as the work-to-benefit ratio at that site was pretty sad—I didn't pay as close attention to such things this year since I didn't feel a need to cover it online, but I have been involved in conversations as well as observed other comments regarding the trades made and not made by the Mariners.

Since July 1st, the M's traded away outfielder A.J. Pollock, pitchers Chris Flexen and Trevor Gott, and five minor leaguers of little impact (the most highly regarded of which is OF Jack Larsen, traded to San Francisco for a Player to be Named Later or other compensation to be determined); no one, including me, seems to think those deals are particularly notable. Pollock was a bust on a one-year contract, Flexen had pitched himself out of a job, Gott was expendable to get Flexen's contract off the books, and no real depth was lost from the minors.

They also released second baseman Kolten Wong and traded reliever Paul Sewald to Arizona. Those are the ones people talk about.

Wong was a disappointment with the M's after coming over in an offseason trade with Milwaukee, but to be fair, he was only given one chance, right at the beginning of the year. He started out slow, hit his high-water mark on May 10th (.195, .287 OBP), and then was given an average of 1.7 PAs per game the rest of the way. He might have fought his way out of the slump, he might not have. We'll never know. He hasn't caught on with another team yet, but I'm sure he will before long, and I'd bet he bats better than .250 with that new club. Still, his departure doesn't hurt the Mariners at all.

The Sewald trade is the one people question. Some think it was throwing in the towel on making the ’23 postseason. I disagree, I think it was a great move, selling high on a player who'll never be more in demand and improving the team long- and short-term.

The return for the M's in these deals was two minor-league pitchers of little consequence, a big-league reliever in Trent Thornton, two PTBNL or cash, and the three guys from the Sewald deal with the Diamondbacks: IF Josh Rojas, OF Dominic Canzone, and Triple-A 2B Ryan Bliss.

Rojas is no help. He basically replaces Wong with worse defense. He's versatile, can play four or five positions adequately, but the M's already have a better player like that in Sam Haggerty, currently toiling in Triple-A with a .321/.406/.580 slash line that makes me shake my head—why is he still down there while the M's keep trotting out Dylan Moore and Rojas? Even José Caballero hasn't been that productive, batting just .188/.275/.250 with a near-30% K rate since the middle of June. I'd much rather have Haggs on the roster than any of those three.

Anyway, though Rojas is meh at best, Canzone and Bliss are good players that just need a chance to prove themselves, and they play positions of need for the Mariners. The Seattle outfield is a mess, with last year's Rookie of the Year Julio Rodríguez the only solid everyday guy in the mix. Teoscar Hernández has been disappointing—though he's shown signs of being his old self of late (batting .302 over his last 10 games)—and Jarred Kelenic got mad and broke his foot while having a tantrum after striking out a while back. Canzone had a traditional development period in the minors, not skipping levels like the Mariners tend to do, and tore it up in Triple-A the last couple of seasons (.939 OPS in 588 ABs) before his recent callup and just needs an adjustment period to find his way in the bigs. Bliss needs a full year at Triple-A to gauge his readiness; he mashed at Double-A, which is promising, but skipping Triple-A is usually a bad move. Still, there's upside to the guy and he should either be a 2B candidate in ’25 or mid-’24 or a good trade chip.

More to the point, relievers in general and closers in particular are, in my view, tremendously overvalued. The number of truly dominant, sustainably effective closers in baseball since the save became a thing is small. There have been maybe a dozen. Half that if you're really strict in your metrics. Every team would like to have Mariano Rivera or Dennis Eckersley at the back end of the ’pen, but plenty of very good teams get by with the sort of effective late-inning relief that lasts for a year or two and/or that is found on some other club's scrap heap. Lots of guys can rack up saves. You know who's 21st on the all-time saves list? José Mesa. Yes, that José Mesa. There are 17 guys that have had 50+ saves in a season and I bet you can't name them all.

The list of relievers the Mariners have used as closers—effectively!—includes names like David Aardsma, J.J. Putz, Brandon League, Tom Wilhelmsen, Steve Cishek, and Mike Schooler. Even Bobby Ayala was decent at it in 1994. Paul Sewald is not out of place on that list, guys that were good for a while then flamed out or just had a couple of fine years in otherwise average careers. Point being, closers are easily replaced and Canzone/Bliss/Rojas is a more than solid return for a name from that list in general and Canzone is more important to the team right now by himself than was Sewald.

Sewald himself was a scrap-heap find. Picked up off the Mets' discard pile, he'd been a middling to poor relief option in New York, 14 losses and a 5.50 ERA over 147 innings. In his first opportunity with the Diamondbacks, Sewald blew the save while surrendering a pair of homers. The Mariners will plug someone else into the role—likely Andres Muñoz, who fits the classic closer "profile"—two-pitch type with fastball near or at 100mph and a favored breaking pitch—a lot more than Sewald did, but scrap-heap pickups like Justin Topa or Thornton might do just as well.

Seattle is now eight games above .500 and a better bet to make the playoffs now than they were a week ago. Good job.

Elsewhere in the baseball world, I happened on a section of baseball-reference.com that attempts to track the effects of Commissioner Rob Manfred's rule changes that went into effect this year. To my great non-surprise, so far the results are not such that it makes me change my opinion on them—on the whole, I still think they do more harm than good.

The pitch clock has shortened the overall time of games. To date in 2023, the average time of game is two hours and thirty-eight minutes. To my mind that's an overcorrection—2:45-2:50 seems about right for an average to me, and that was the norm from 1998, when MLB expanded to its current 30 team structure, through about 2011. From 2012 through last year it hovered around the three-hour mark. So Manfred has cut 22 minutes or so from the typical game, the most significant effect of his changes, mostly by reducing the time between the start of one plate appearance and the start of the next by 15-20 seconds. (The most striking number might appear to be the percentage of games over 3.5 hours—a minuscule 0.3% this year—but some of that is because of the inane, detestable zombie-runner-in-extra-innings rule that should be excised from the game immediately if not sooner, along with the at-least-equally detestable designated hitter rule. The zombie runners were a thing in 2020-2022 also, and there were a lot of 3:30-plus games in those years, so one could infer the pitch clock to be the primary factor, but I'd need to see data on the number of extra-inning games in each year.) I submit that this can be tweaked to make the change less severe by making the pitch clock a standard 20 seconds, not 20 seconds with runners on and 15 without.

The larger bases and the restriction on pitchers keeping runners close to the base has resulted in an uptick in stolen base attempts to roughly 0.9 attempts per game, or about what it was in 2012. The big difference is in the success rate: 80%, or about 10% higher than used to be the norm when attempts were that frequent. (Even my favorite team of all time, the 1985 Cardinals, which has that honor in part because they stole tons of bases, had a then-elite success rate of 77%.) This I attribute to the bigger bases and I feel like it cheapens the play. (Although, it may also be attributable to the newish more-common practice of catchers resting on one knee; the traditional catcher crouch is faster when it comes to getting a throw off to second base.) I love me a stolen base, don't get me wrong, but it loses something when it's not just the speedy guys that can get them.

The change that netted almost zero change is the ban on defensive shifts. Maybe a few individual players have benefitted form this, but overall it's been a big nothing:

| Yr | Gms | BA | BAbip | H/9 | 1B/9 | HR/9 | K/9 | R/9 | Ground Ball BA | LHB Ground Ball BA | RHB Ground Ball BA | Line Drive BA | LHB Line Drive BA | RHB Line Drive BA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 3364 | .248 | .297 | 8.52 | 5.44 | 1.21 | 8.73 | 4.66 | .248 | .240 | .253 | .642 | .648 | .638 |

| 2022 | 4860 | .243 | .290 | 8.29 | 5.41 | 1.09 | 8.53 | 4.35 | .241 | .226 | .250 | .631 | .628 | .633 |

| 2021 | 4858 | .244 | .292 | 8.34 | 5.28 | 1.26 | 8.90 | 4.65 | .241 | .232 | .248 | .637 | .636 | .637 |

| 2020 | 1796 | .245 | .292 | 8.40 | 5.28 | 1.34 | 9.07 | 4.85 | .237 | .215 | .255 | .643 | .637 | .647 |

| 2019 | 4858 | .252 | .298 | 8.71 | 5.38 | 1.40 | 8.88 | 4.86 | .242 | .233 | .247 | .632 | .633 | .632 |

| 2018 | 4862 | .248 | .296 | 8.49 | 5.45 | 1.16 | 8.53 | 4.48 | .246 | .235 | .253 | .626 | .627 | .624 |

| 2017 | 4860 | .255 | .300 | 8.78 | 5.60 | 1.27 | 8.34 | 4.70 | .249 | .241 | .254 | .632 | .632 | .632 |

| 2016 | 4856 | .255 | .300 | 8.79 | 5.72 | 1.17 | 8.10 | 4.52 | .249 | .238 | .257 | .659 | .654 | .662 |

| 2015 | 4858 | .254 | .299 | 8.73 | 5.81 | 1.02 | 7.76 | 4.28 | .249 | .241 | .255 | .644 | .643 | .645 |

| 2014 | 4860 | .251 | .299 | 8.58 | 5.87 | 0.86 | 7.73 | 4.08 | .252 | .244 | .258 | .657 | .648 | .664 |

| 2013 | 4862 | .253 | .297 | 8.68 | 5.86 | 0.96 | 7.57 | 4.18 | .244 | .238 | .248 | .674 | .674 | .673 |

The ’23 numbers are more than ’22's, sure, but you only have to go back to 2016-2017 for higher ones across most columns (or lower in the case of Ks per 9 innings). Was the shift really that big a factor from 2017-2022 or is that dip within a statistical expectation?

Obviously, less than one full season's worth of stats isn't going to be definitive of anything, we'd need to see a few years' accumulation to really see if anything really changes much.

No Comments yetGet off my lawn, pitch clock

As I have previously mentioned, I am, shall we say, not a fan of baseball commissioner Rob Manfred. He's terrible. And his new rules imposed on the game, both prior to this year and the new batch in 2023, rankle me. Well, OK, the three-batter minimum for pitchers is fine. But about most of the rest, I am rankled.

Still, this year's batch of changes—the pitch clock, the shift ban, the pickoff limitations—are being met with overwhelmingly positive reaction from people who choose to opine on such things. This also rankles me, but the reasons are more amorphous and vague.

Take Pos and Schur's effusive praise of the new normal. Joe Posnanski and Michael Schur have a podcast ("The Poscast") I find very entertaining (except when they go too long on about non-baseball sports). This week's Poscast was mostly about the new rules and, as Schur put it, he finds them "an unmitigated success." Pos calls the new setup "so awesome" and thinks criticism of it is "insanity." I generally love these guys, but this is…excessive.

They illustrate their position by comparing the pitch-clock setup to the extreme of the previous norm, referring to a side-by-side video someone posted of an entire half-inning of a spring training game from this year alongside a clip of Pedro Baez facing the Cubs in the postseason a few years ago that encompassed a single pitch over the same span of time. Yes, that Pedro Baez example is excessive. That wasn't good and making such an extreme sequence impossible isn't bad in and of itself. But it wasn't a representative AB, it was very much an outlier.

They further cite comparisons to other sports to justify the pitch clock. "Imagine basketball without a shot clock," Schur says. Well, Michael, I don't know or give a damn about basketball. Or football or hockey or any of the other examples he cites. A more frenetic pace might well be appropriate for those games, I don't know. Those sports are not baseball. Baseball is unique. Those arguments mean nothing to me. Eventually he gets back to baseball and makes arguments that mean something, and I respect those, though I disagree with the idea that eliminating the ability of the pitcher to effectively hold a runner is a net good.

Posnanski reminds us that these new rules are a correction, the idea is to return the game to what it was 35, 40, 50 years ago when batters did not step out of the batters' box all the time and pitchers didn't consider his next delivery for a minute before getting into the stretch. And defenses didn't move around the field because of a batter's spray chart that says he never hits to the opposite field. And that, he says, is what we want.

That point I agree with. I do want the game to be played more like it was in the ’80s and ’90s. I just don't like this methodology.

Maybe I'm just a grumpy old man and once I give this a chance I'll be fine with it. Entirely possible. I freely admit that my resistance to accepting the pitch clock and shift ban is tied inextricably to everything else Rob Manfred has done since he took over as commissioner—ads on the field; ads on the uniforms; proscribing who can pitch and who can't; devaluing the season with extra Wild Card playoff slots that are just as good as winning a division; the fucking "zombie runner" in extra innings; and the worst of the worst, the "universal DH"—and giving him even indirect credit for anything feels like having to eat a bowl of moldy nutraloaf. Had Manfred not screwed around so much with these awful things already, I'd likely be closer to Pos and Schur's position.

Yet, having watched some spring training action this year, it does feel rushed. Not frenetic, necessarily, but maybe a little too fast. There is value in having a moment to ponder the next pitch selection for those of us who, you know, pay attention. 15 seconds might be too short a span. When a runner is aboard and the clock extends to 20 seconds it's not bad, that feels proper. It's early days, of course, and it's spring training, but part of the goal for these changes is to create more offense and what I'm seeing is actually more striking out. Batters aren't ready when they swing. That'll change as we move forward, the adjustment period is going to be at least a few weeks of in-game at-bats, but I think 15 might need to be, say, 18 or 20.

Practically speaking, I will not miss the infield shift. I do not like banning it, but batters have unequivocally refused to combat it. In the early days of infield shifts being common, Ken Griffey Jr. would take advantage of it once in a while and bunt to the empty side of the field for an easy hit. Skilled contact hitters could beat it. But that went away, analytics decreed that batters should just keep on trying to pull the ball and hit for power, so defenses started shifting on nearly everybody.

Schur describes the shifting-for-everybody as an "overcorrection" to the steroid era. I see what he means, but I don't like that description at all, because the underlying problem is so many more batters swinging for homers and that hasn't been corrected for at all. Emphasis on power hitting is the underlying problem as regards the infield shift. That plus emphasis on power pitching is the underlying problem behind excessive strikeouts.

Move fences back. Make homers harder to hit and make the outfielders cover more ground—which is also more like things were in the ’80s—and you'll see fewer homers but more singles, doubles, and triples. And when batters (one would hope) stop swinging for the fences all the time, fewer Ks. And less incentive for infield shifts.

The shift ban makes that last bit moot, there's no way that rule is ever going away now that it's in place. We're likely stuck with the pitch clock forever too, and with luck over time it'll fade into the background and not be such a distraction.

But I will campaign until the end of time to do away with the Manfred Man zombie runner and the worst rule of all, the designated hitter.

No Comments yetAnother rant about Rob Manfred

Hey Rob, you're bad at your job and nobody likes you.

Hey Rob, you're bad at your job and nobody likes you.

We're getting close to baseball season 2023. Which is, for some of us, all kinds of fun and cool. However, because we live in the Rob Manfred Era of Major League Baseball, it also means we need to prepare for what is now an annual period of adjustment to the new ways Commissioner Manfred has decided to screw with the game and piss us all off.

I've written plenty about Rob Manfred's penchant for damaging the game of baseball over at that-other-site-I-used-to-run-that-is-now-defunct-and-one-day-I-will-put-selected-posts-up-here-as-a-form-of-archiving. He is without a doubt the worst person to ever occupy the office of Commissioner of Baseball. He doesn't appear to even like baseball. He's all about incessantly tweaking anything he can think of if there's the slightest possibility it might mean more money for team owners in the short term. (Fuck the long term. Compared to Manfred, even Mr. Magoo has telescopic HD x-ray vision.)

Ever since Manfred took over the job, he's been altering the game in both large and small ways. To date it hasn't gone so far as to make the game unrecognizable, but give the guy a few more years and we'll be watching blernsball or Calvinball.

A lot of the alterations are "behind the scenes," dealing with money stuff and organizational rules about how long a stint on the injured list is, how the amateur draft is conducted, how many times a player can be shuttled back and forth to the minor leagues, that sort of thing, and those might be good or bad but they don't actually affect the game as it's played on the field from first pitch to last out. It's the on-field stuff that grates my cheese the most.

2023's new rules include:

- A pitch clock

- Bigger bases (18" square rather than the traditional 15")

- Restrictions on where defenders may position themselves

- Severely limiting what a pitcher may do to hold a runner close to a base

This, of course, is on top of other rules that were implemented since 2019, which include:

- The automatic intentional walk

- Three-batter minimum for pitchers

- A limit on how often catchers can go to the pitcher's mound

- Proscriptions on what players may and may not pitch and when

- The "zombie runner" in extra innings, which was supposed to be a temporary COVID-era measure that has, as of last Monday, been made "permanent."

- The metastasization of the cancer known as the designated hitter rule

- Diluting the season with added Wild Card teams in the playoffs

The only new rules I don't detest are the mound-visit limit and the three-batter minimum. Those actually add an element of strategy while addressing Manfred's complaint, which was so-called "dead time" while pitcher and catcher discussed tactics and too many pitching changes. Otherwise, these changes all completely suck. I could go into why for each of them, but I'll spare you that for now.

Manfred's stated goal with all these tweaks and changes is to "increase the pace of play," by which I think he really means "make the game more accessible for those with attention-deficit disorder." (Come to think of it, Manfred himself may well have ADHD, which would explain some of this nuttery.) His actual goals are open to speculation, but you would not be out of line to think dumbing things down is high on the list.

Unquestionably the experience of the game has slowed, for lack of a more accurate shorthand, over the past couple of decades. Relief pitching has become far, far more prevalent and that brought along the "dead time" of more pitching changes during games; existing rules regulating batters stepping out of the batter's box were not enforced and more and more players developed Nomar Garciaparra-like habits; the steroid-era created so much more emphasis on home-run power that more and more and more players adopted approaches to hitting that made "This misnomer of a phrase refers to a plate appearance resulting in a strikeout, a walk, or a home run. A “three-true-outcome hitter” is statistically unlikely to do anything else in any given time at bat.three-true-outcome" players common rather than rare; certain matchups like Yankees-Red Sox came to have so many mound meetings that if you worked it right you could time a trip to the concession stand during one and not miss a pitch. And, of course, TV demanded more commercial time, about which there's only so much anyone would be willing to change.

Imposing some sort of "correction" on the game to address this slowing isn't in and of itself something I would oppose categorically. On the contrary, I would very much like to see the obsession with home runs fade away and contact-hitting return to favor. That would reduce the number of pitches per at-bat, reduce the incentive for defenses to employ position shifts, even cut down on relief usage by allowing starting pitchers to go deeper into games before tiring. But you don't accomplish that by imposing a pitch clock; or, if you do, it's a side effect rather than the plan.

The pitch clock might work out OK in the end, but it sure seems problematic. It's pretty brief—not so much for the pitcher as for the batter; pitchers will have 15 seconds to start their throwing motion (20 if there are runners aboard), batters must be in their stance and “alert to the pitcher” within eight seconds. The problems come in when the time is exceeded and a ball or strike is added to the count to penalize whichever player wasn't ready in time. Imagine that happening during a tense moment in the late innings of a tight game. One effect might be that pitchers don't throw as hard, which would be welcome. Another might be that pitchers get hurt more often, which would not.

Larger bases...eh, they look weird, but this will quickly become "normal" and not be much of a thing. It's just a way to increase offense, get more safe calls, but it might make for fewer collisions and injuries to first basemen. I can live with it.

The restriction on pick-off attempts is the worst of these new changes, it's a naked tipping of the scale away from the defense in favor of baserunners. It'll turn every pitcher into Jon Lester, except he won't even be able to step off the pitching rubber or hold before the pitch to keep a runner close to the base. It's a much more significant change to the game than I think anyone realizes at this point. Don't get me wrong, I love stolen bases—my favorite team of all time is the 1985 Cardinals, after all—but don't cheapen them. Cat-and-mouse between a pitcher and a Lou Brock or a Vince Coleman on first was part of the tension, part of the thrill of getting a steal. Now it's gone.

Manfred has done away with the pitcher-runner tension, eliminated all strategy related to pitchers batting and worsened the existing DH rule to favor Shohei Ohtani alone while enacting rules that make future Ohtani-like "two-way" players nearly impossible, imposed radical restrictions on who can play where and in what circumstance, destroyed the potential for epic extra-inning games, cheapened the meaning of the long season schedule with almost participation-trophy tiers of playoffs, and that doesn't even get into his penchant for negotiating in bad faith, his pathetic response to cheating teams, his dishonest remarks to the press, basic stupidity about the game, and utter disregard for fans and consumers of the sport—his ostensible constituency as commissioner of baseball.

Or is it even ostensible? The fact of the matter is that ever since Bud Selig, then the owner of the Milwaukee Brewers (and thief of the Seattle Pilots), succeeded in his coup d'etat to overthrow Commissioner Fay Vincent to install himself in the position in 1992, there has been no figure in the MLB hierarchy that represents the baseball consumer. Selig made the job into a mouthpiece for ownership, an autocratic office firmly entrenched with championing the interests of club owners and club owners only. Calling the position "Commissioner of Baseball" is improper. Needs a new title, like "Agent of Greedy Asshats." I mean, there isn't a "commission" anymore. There aren't even league presidents to mediate.

The Commissioner position was created (well, technically reformed, but for all practical purposes created) in the wake of the Black Sox scandal and ensuing threats by National League officials to effectively destroy the American League by absorbing big-city AL teams into its own circuit. To contend with the public relations nightmare, an outsider was brought in to safeguard the national pastime as chair of the reimagined National Baseball Commission, which was to be made up of, by design and specific intent, people not otherwise affiliated with the business of professional baseball. That chairperson was Kennesaw Mountain Landis, who insisted on being a commission of one and, as he knew the lords of the Majors needed him more than the other way around, negotiated himself ultimate authority as the commissioner to act "in the best interests of baseball" as a whole, not of club owners or ballplayers or media figures or any other isolated group. Essentially, to represent the consumers, the public, as well as mediate disputes, regulate conflict, and be a check on ownership (players of the time didn't have any power to check). Subsequent commissioners had the same authority, purview, and requirement to be otherwise unaffiliated with the business of the leagues. Until Bud Selig's coup, which almost immediately begat the 1994-95 strike. (The revisionist history of Selig's reign reminds me a lot of how people talk about George W. Bush—"he kept us safe." You know, except for that one time. "Selig presided over great growth of the game," you know, except for that one time.)

Manfred claims to have the fans' interests at heart. “I think that the concern about our fans is at the very top of our consideration list,” he actually said with a straight face during the last collective bargaining sessions with the players' union, after which he imposed a lockout and canceled the beginning of the 2022 season.

Baseball doesn't have a commissioner, it has an agent of greed, and in this case one that doesn't like the sport and wants to make it something else.

Alas.

I'm trying to keep an open mind on the pitch clock. But I suspect the law of unintended consequences will rear its ugly head and it'll be bad.

No Comments yetNew Rules

Commissioner of Baseball Rob Manfred, laughing maniacally as he continues to mold the game of baseball like a toddler pounding a lump of play-doh into an unrecognizable blob

Commissioner of Baseball Rob Manfred, laughing maniacally as he continues to mold the game of baseball like a toddler pounding a lump of play-doh into an unrecognizable blob

He's at it again.

The Commissioner of Baseball, one Robert D. Manfred, has made it his mission to turn the game he is the current custodian of into something all of its previous custodians would not recognize. So far, he has instituted a swarm of smallish rule changes as well as a few huge ones to Major League Baseball and he's got more coming next year.

If I may paraphrase J. Jonah Jameson, the man is a menace.

Manfred simply does not like baseball, at least not in the sense of the game as a whole, balanced concept that requires strategic thinking and intellectual trade-offs to navigating the game. Nor does he value competitive integrity or the richness of detail. He likes simple. He likes not to have to think. He likes short attention spans.

Thus far, the Manfred regime has given us:

- The no-pitch intentional walk

- The "universal" designated hitter (ugh)

- Requiring teams to declare in advance who is a pitcher and who is not and imposing a limit on how many pitchers a team can carry

- The "zombie runner" in extra innings (which some of a certain age have humorously taken to calling the "Manfred Man")

- An entirely avoidable and self-inflicted labor stoppage that delayed the opening of this season

- Expanded playoffs, the first taste of which we'll get next month, which now allows nearly half the teams in the Majors into the postseason and devalues both the season as a whole and the winning of a division title

- Advertising on the fields, not just on stadium walls and scoreboard signage, but on the fields themselves (in foul territory and on the pitcher's mound)

- Advertising on uniforms, which we'll start to see in this year's playoffs and will be an everyday thing starting next year

- The three-batter minimum for pitchers (this one I actually don't have a problem with, though the reason it came into being is no better than the rest of this)

- Ugly unis for the All-Star Games

- Effective acceptance of the Houston Astros' cheating scandal with virtually no repercussions for the perpetrators

Starting in 2023 we will also now have:

- A pitch clock. No longer will baseball be the game with no clock, there will be one to mandate that pitchers and batters move things along regardless of circumstance. Well, not quite regardless—the clock will have 15 seconds on it when the bases are empty, 20 when a runner is on base. If a pitcher takes too long before delivering a pitch, a ball will be added to the count; likewise, if a batter steps out or isn't ready to go within eight seconds (he will be permitted to request a time out once per plate appearance) a strike will be added. Further, only 30 seconds will be permitted between batters; if the next batter in the lineup isn't ready to go 30 seconds after the previous play, he starts with a count of strike one. Despite this having been experimented with in the minor leagues in recent seasons, it remains to be seen how this will play out; it might be OK. Used to be that the players that were slower to deliver a pitch or who took "excessive" time at the batter's box between pitches were relatively rare, but today they're more commonplace and it will at least be interesting to see if this cuts down on so-called dead time without disrupting anything else. But the law of unintended consequences pretty much guarantees there will be issues.

- A limit on how often a pitcher can try to pick off a baserunner. This is a clear and blatant declaration that pitchers should not care about runners; Manfred has openly said he wants to "create more action," which apparently means preventing a defense from trying to get runners out. I love the stolen base, it's one of my favorite plays, but all this does is cheapen it.

- A restriction on where defenders can play. For the history of the game, only the pitcher and catcher were required to be at any specific point on the field. No longer. Two infielders must begin each play on either side of second base and forward of the outfield grass. No more shifting three infielders to one side, no more moving your second baseman into the outfield, no more four-outfielder defenses. This also is based on Manfred's desire for "more action," and because batters as a whole have chosen not to combat defensive shifts over the years, it probably will result in more base hits as fielders will be prevented form playing where they should be allowed to play. The language of the rule is vague enough that someone will at some point cause it to be clarified; it's intention is to maintain the restriction until "the pitcher releases the ball," but it also says the infielders "may not switch sides during the game." So when J.P. Crawford makes a great play running from his shortstop position to flag down a hard grounder on the outfield grass at the right side of second base, is he in violation of the rule? I think not, but someone will exploit the language to challenge such a play.

- Larger bases. The bases on the field will grow from 12" square to 15" square. This will be odd at first but quickly folded into expected norm, I think. Again, this is to give offenses a boost by making it that much harder to get baserunners out. The one positive to this is the extra area will give first basemen a little more of a safety margin on potential collisions on close plays at first, but this could have been accomplished simply by extending the base an inch or two into foul territory instead.

- The completion of the destruction of the American and National Leagues as anything more than labels. Manfred's predecessor started this process in the ’90s, but with this year's adoption of the designated hitter rule (pause for dry heaves) by the National League and next year's change in the schedule that has every team play every other team in both leagues during the regular season, the merger from two distinct entities into one is concluded.

Not one of these changes was made with the good of the game in mind. Every one has been with an eye toward getting bigger short-term profits for a business that already rakes in $10 billion in annual revenue.

Manfred believes that the game needs to be dumbed down and sped up in order to attract younger viewers with short attention spans. He thinks that making the game into something else will get him bigger television ratings. He things more playoff games will mean more TV money overall. He thinks that the baseball audience likes hitting and doesn't care about fielding and by making these changes to unbalance things a bit that people who do not watch baseball will decide they now will watch baseball.

Which is just dumb.

You don't say, "hey, non-fans, I know my game is slow and boring because it requires thinking and thus doesn't appeal to you, so I've dumbed it down closer to your level and made it a little bit more frenetic! You like that, right?" and expect to convert everyone. People who come to baseball come to it because it's different. Because if you know what's going on, that so-called dead time isn't usually so, there's actually tension and stuff going on strategically.

A pitcher worried about a stolen base threat on first was actually valuable to both sides if you understood the situation. Having the pitcher in the lineup made for decisions during the game and a thought process about building your team and planning a game that are just wiped out now. Having the option to dare a batter to hit the other way by leaving a whole third of the field undefended was an opportunity for both teams to exploit. Gone. Sure, few if any people will miss the Nomar Garciaparra-like ritual of stepping out of the box, re-fastening the batting gloves, and taking three practice swings like a mini-hokey-pokey before every pitch, but not many guys did that.

Frankly, the 2023 changes aren't going to be as big a deal as the ones we're already seeing now (or have known are coming, like the jersey ads), which are far more damaging. The pitch clock, the shift ban, sure, I object to them on principle, but in the old days shifts were rare and few players took a lot of time between pitches anyway, so it won't seem too bad. The step-off rule, that I hate and can't figure why any pitcher would approve of it.

Still, I'd accept it all gladly if Manfred would use his new, negotiated ultimate power to impose changes without union approval to abolish the DH and consign it to a fiery death.

No Comments yet